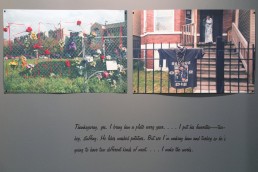

Street-side memorials appear in Chicago neighborhoods after violent losses—marking death spots. In 2015 and 2016, we set out to understand these memorials’ intimate and invisible stories. We wanted to learn what sidewalk memorials mean to the people who build them and to members of the community. Memorials contain private meanings easily missed from a moving automobile. Much of the public therefore lacks direct access to the emotional depth. We wanted to spend time with these structures and the people who built them, and to listen to their stories. We were also interested in the fact that these memorials are somewhat new to the Midwest and the ‘whats’, ‘hows’ and ‘whys’ of this cultural shift.

Ferrella considers himself a “recovering emergency medicine physician.” He worked for thirty years in Madison, Wisconsin, as a trauma specialist. Twenty years ago, he was the attending physician when a young high school woman arrived in the emergency room with severe traumatic injuries. A car had hit her and her friend as they crossed the street in front of East High School in Madison, Wisconsin. Both did not survive. Their deaths led to a long-lived evolving roadside memorial, which Ferrella found inherently beautiful, intimate and powerful. This experience prompted him to begin his photographic journey of documenting these sites throughout Wisconsin. This endeavor has been ongoing for over 20 years. For a better look at that project go to www.wisconsinroadsidememorials.com.

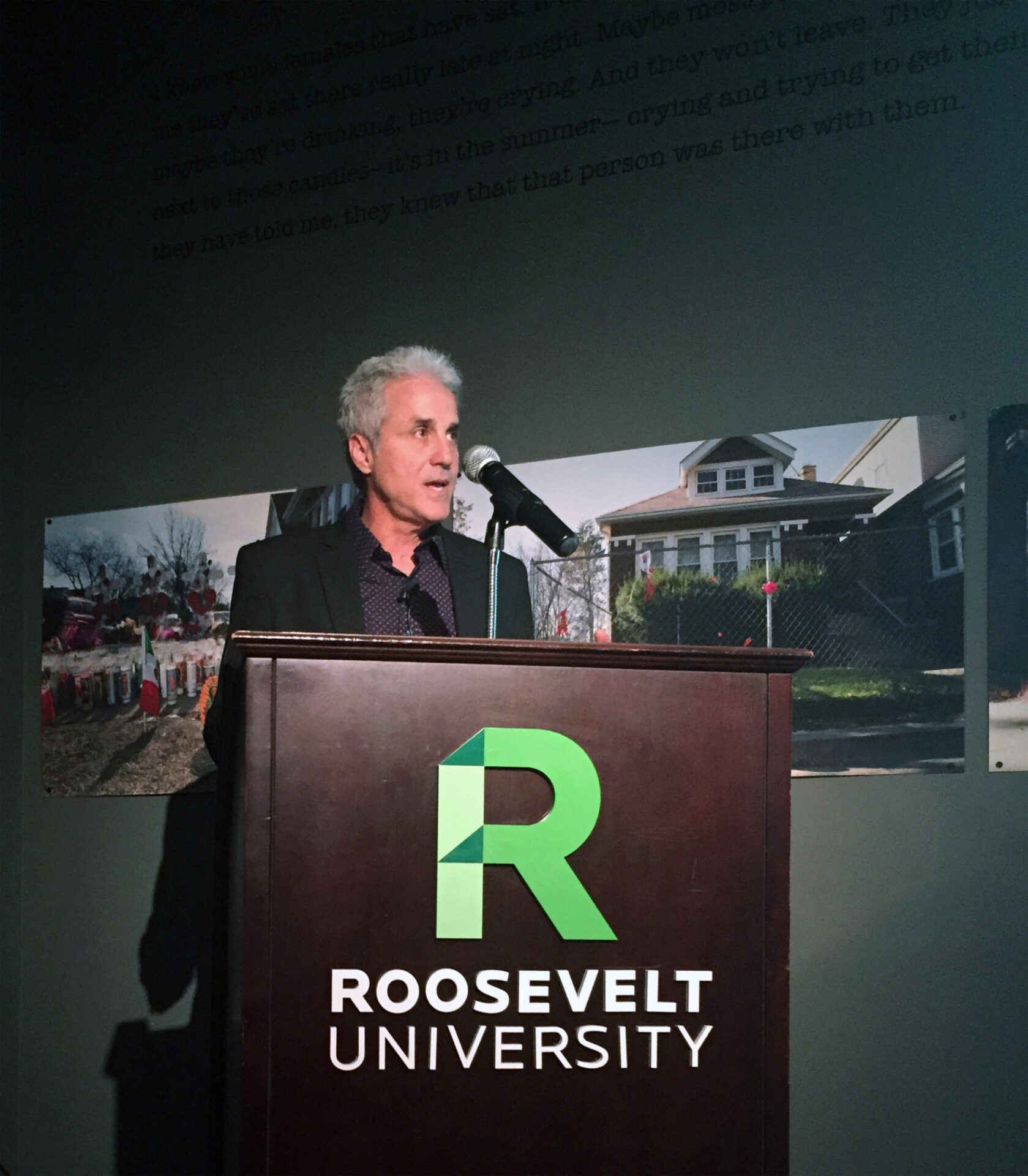

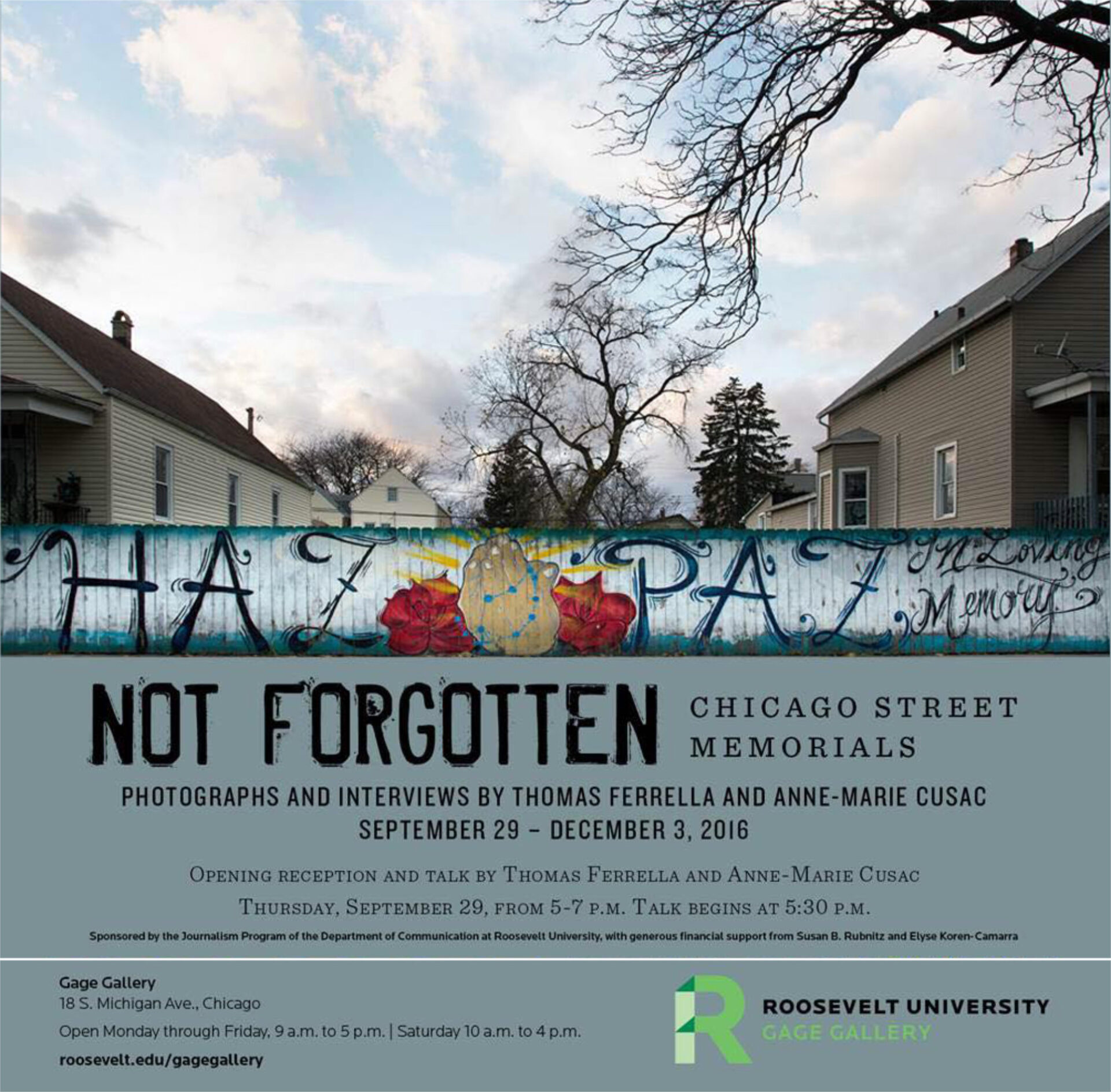

Through another art project of Ferrella’s, we met as collaborators and he invited me to tell the stories behind these Wisconsin memorials. The Wisconsin project made Cusac think about the ways that people and communities grieve in her own city. She lives in South Evanston and teaches at Chicago’s Roosevelt University. Cusac knew of memorials on her streets and soon learned that if she mentioned the project to acquaintances, they would become more attentive. She became aware of blocks with multiple simultaneous memorials. A meeting was arranged for an exhibit of the Wisconsin project with Mike Ensdorf, curator of the Gage Gallery. What came of that meeting was a shift in gears and the outcome was to pursue a similar project in Chicago with the emphasis on murder sites and a show at the Gage Gallery. The resulting project is NOT FORGOTTEN: Chicago Street Memorials.

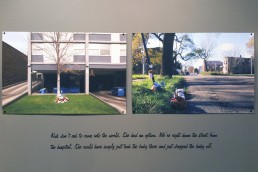

Sidewalk memorials frequently appear at murder sites. We didn’t know this when we started, but the fall of 2015 and spring of 2016 would prove significant seasons in this gun-troubled city. In the fall of 2015, we heard of a “hot time” in some of the neighborhoods we were visiting. The homicides that year numbered 470, with 2,939 people shot, according to the Chicago Tribune, which reported, “Chicago had the most homicides of all U.S. cities in 2015, its worst year since 2012, when about 500 people were killed.”

The violence spike continued. By late May, The New York Times commented, “Already embroiled in a crisis over race and police conduct, Chicago now faces a 62 percent increase in homicides. Through mid-May, 216 people have been killed. Shootings also are up 60 percent.” By late summer 2016, the city had more than 2,500 shootings for the year and more than 400 homicides, reported the Chicago Tribune.

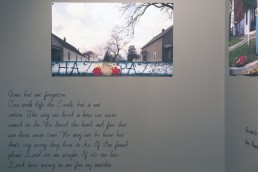

Neighborhoods with high levels of gun violence reveal a geography of violent loss. In the Little Village, community activists called one street, “the shooting gallery.” On one corner there were three memorials, with others just a short distance away. But in the minds of the activists there were many others. As we travelled these neighborhoods with our guides it was not unusual for their memories to be triggered and subsequently sharing their personal witness to decades of other tragedies.

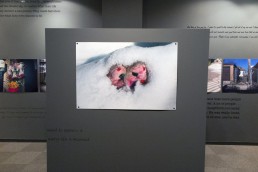

Ferrella created a photographic record— over a thousand images of memorials that were in many cases changing even as he recorded them. In the case of the Gage Park murders of a family of six, the large front yard memorial accumulated flowers and candles while Ferrella was photographing. The Little Village mural we called “Haz Paz” disappeared in the weeks between our visits, the fence between two houses repainted. Change seems to be part of the point. Once-bright ribbons turning gray, crinkled letters to the departed, stuffed animals staring from a snow bank, and other objects of remembrance encased in plastic wrap or plexiglass—all these providing a poignant record.

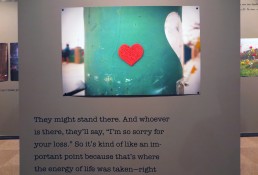

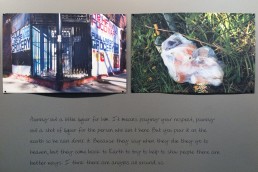

But memorials don’t just fall apart and vanish. They can also be locations of ritual, repetition, and celebration. We learned of multiple memorials loved ones rebuilt after other people—rivals or police—kicked them apart, removed them, or even burned them down. Many memorials reappear annually on the date of death. In Englewood, we encountered people who devote a portion of their emotional lives to the work of grief—moving from memorial to memorial, month by month, celebrating death anniversaries and birthdays. While memorials can appear modest and weathered, they serve a purpose in the grievers’ emotional and mental health, and in community healing.

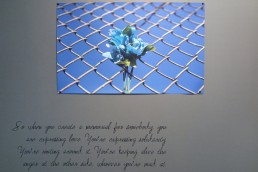

We heard again and again about the importance of the death spot—the place where the last breath left the loved one’s body, where the earth absorbed the loved one’s blood. Many we interviewed indicated that the death place offers a more personal access to the dead. Some also said the memorials were warnings to people in the community to be careful.

Ferrella’s interest was in part aesthetic. He considers them as free-form art installations. Lacking curators and architects, they change as mourners arrive, add objects, and move things about. They decay, the weather contributing its own mystery and patina. The memorials change the landscape, and can appear surreal in well-manicured yards. It can be difficult to comprehend that violence and trauma recently erupted on a curbside that at the moment appears serene.

The practice of roadside memorialization is ancient; some scholars see antecedents in Greek and Roman cultures and suggest the practice traveled to the Americas via Spain. This may explain why Ferrella has witnessed these memorials throughout his travels in Central and South America as well as the southwest United States well before they ever appeared in Wisconsin and the Midwest.

Our tools are those of the documentarian: cameras, audio recorders, notebooks, and our own openness to the city and to people. We did not intend this project as comprehensive or scientific. Instead, we aimed to humanize Chicago’s street memorials, to understand their meanings to the extent possible, and to tell their stories. We did not travel to all parts of Chicago that have high murder rates. In some cases, this was because our contacts told us the memorials disappear quickly in those neighborhoods. In other cases, we simply did not hear rumors of memorials in those places. We would have been happy to continue this work for years—it is that moving. Many people opened their homes and their hearts and minds to us. We feel gratitude for their trust and their words. We were touched that people thanked us for asking questions. They were grateful we were paying attention, that anyone was paying attention. They consider this to be a war zone, the “killing fields” as we were told. A modern day atrocity that is going unnoticed by the powers that be and has become an accepted part of their communities. The new normal so to speak.

We intend this exhibit as a snapshot record of the grief and the love present in humble and transitory objects on the sidewalks of Chicago. As another form of memorializing these victims and to not forget! We extend this project with love as our own memorial to those memorials. We feel that this preserves their value, offers a glimpse of their emotional depth and helps us not to forget.

Anne-Marie Cusac, Professor of Journalism

Thomas Ferrella, M.D.

September 2016

A special thanks to Mike Ensdorf, the Gage Gallery, Roosevelt University, Ceasefire and Brother Jim Fogarty, also to all of the people that shared their stories. We are grateful.